A discussion on discussion

I recently watched a discussion between 2 people on the issue of immigration concerning European countries, mainly Italy and the UK. This “discussion” turned argument was during a panel on immigration between the moderator and one of the panelists. Ironically, it was the so-called moderator instigating much of the aggression, although badly handled by the panellist who proceeded an attempt to talk over the moderator (who had tried to interrupt them), not attempting in the slightest to listen.

This is one of the key problems of political discussions where tensions are built up due to differing opinions that are badly managed such that both members of the discussion seem to end up polarised (and often fighting vigorously for something inconsequential or tangential to the original point).

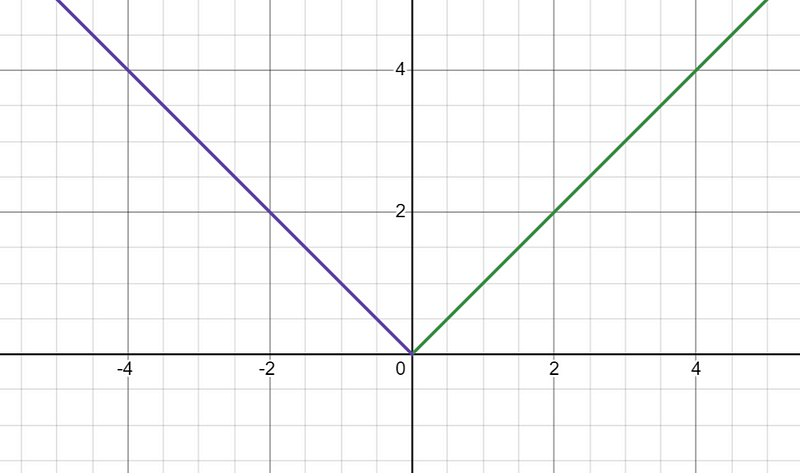

Plotting such a discussion graphically would look something like the following:

Where each line represents a person in the discussion, the distance between the lines how much they agree and the y-axis duration of the conversation.

Now let me propose an idea I first learnt from the psychiatrist Dr Alok Kanojia. This is a way of conversation which allows you a) to understand what the other person is saying (better) and b) for the other person to understand you better. By no means is this a ‘trick’ or strategy to convince, coerce or beguile someone into agreeing with everything you say but it is an incredibly useful tool that you should use whenever having a discussion, particularly difficult ones, to ensure proper communication.

Don’t give your two cents. (yet).

Let’s say that the person you are talking to you gives an opinion. Hear them out. Don’t go barging in with whatever you were cooking up while they were talking (whilst probably not listening to them and just trying to remember some overused rhetoric and talking points you heard online). So now that you have listened to what they said, repeat it. Ask them if you understood them correctly.

Bad example:

OTHER PERSON: I think Israel is wrong for what they’re doing in Gaza.

YOU: Nah they have a right to retaliate. Any other country would do the exact same thing in that scenario.

You see here that both parties have now polarised and have taken up opposing stances on the emerging battleground. (How not to have a family dinner)

Good example:

OTHER PERSON: I think Israel is wrong for what they’re doing in Gaza.

YOU: You think Israel is wrong for what they’re doing in Gaza? huh

In this case, you haven’t taken up an aggressive stance, just asked them to expand on their initial statement. This can be done in other ways than repeating what they say such as “Oh, tell me more” or asking them to specify such as “I understand you think Israel is wrong overall, but what about x” where x could be their occupation before October 7th or their disproportionate retaliation or to generalise it should be something more specific or a deviation from the original statement that you could agree on.

In the previous good example, I personally would’ve said “Oh yeah I 100% agree with you that Israel has done so many things wrong with Gaza…”, making it abundantly clear that I am agreeing with them on something, not only allowing me to ‘be on their side’, aligning myself as a friend rather than a foe but also to set myself up for a deviation to establish new ground. THIS is the bit where you can now give your opinion. “… but what do you think about their right to retaliate?”. Now the other person can clarify their view.

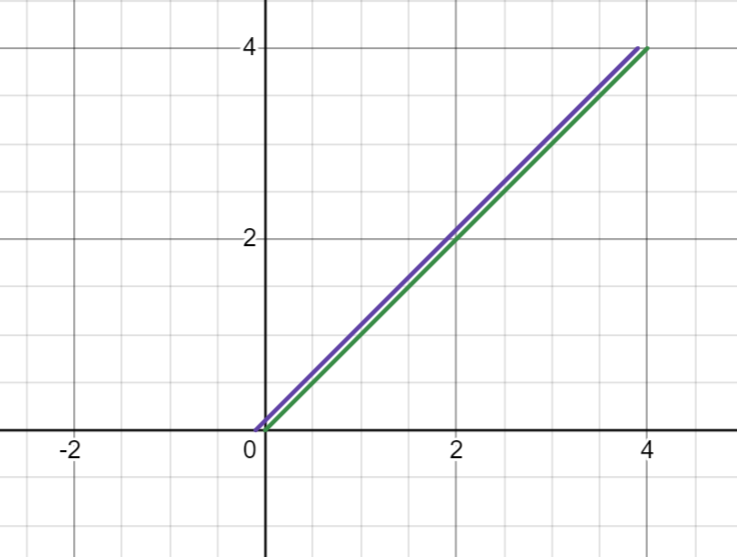

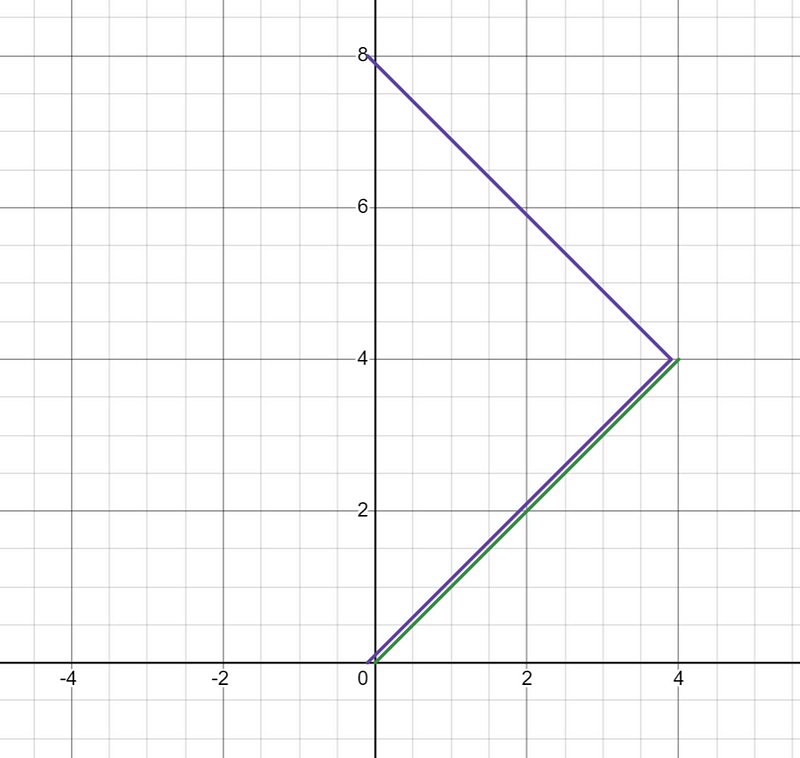

They can do this because they are at the same point as you now, as can be seen from the graphical representation.

Using this method allows both participants to partake in a discussion where both sides listen and come to find common ground. What’s so great about this method is that only 1 person needs to know this and the other person can be none the wiser and it still works.